This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

In this post, we look at the types of embedded payloads that attackers leverage to abuse Microsoft OneNote files. Our analysis of roughly 6,000 malicious OneNote samples from WildFire reveals that these samples have a phishing-like theme where attackers use one or more images to lure people into clicking or interacting with OneNote files. The interaction then executes an embedded malicious payload.

Since macros have been disabled by default in Office, attackers have turned to leveraging other Microsoft products for embedding malicious payloads. As a result, malicious OneNote files have grown in popularity. The OneNote desktop app is included by default in Windows in Office 2019 and Microsoft 365, which can load malicious OneNote files if someone accidentally opens one.

We find that attackers have the freedom to embed either text-based malicious scripts or binary files inside OneNote. This offers them more flexibility compared to traditional macros in documents.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed above through the following products:

Table of Contents

Background

Methodology

Payload Types and Average Size Distribution

Presence of Images in Malicious OneNote Samples

Analysis of an Embedded EXE Payload

Conclusion

Indicators of Compromise

Additional Resources

Background

Microsoft OneNote is a digital note-taking application that is part of the Microsoft Office suite. A OneNote file is essentially a digital notebook where people can store various types of information.

Additionally, Microsoft OneNote allows people to embed external files, enabling them to store files such as videos, images or even scripts and executables. However, Microsoft has started blocking embedded objects with certain extensions that are considered dangerous within OneNote files running on Microsoft 365 on Windows.

However, attackers often abuse the ability to embed objects by planting malicious payloads. Malicious OneNote samples typically disguise themselves as legitimate notes, often including an image and a button.

Attackers use images to draw people’s attention, and they rely on unsuspecting people clicking buttons to launch malicious payloads. This technique is popular for payload delivery as it leverages people’s trust in legitimate note-taking applications.

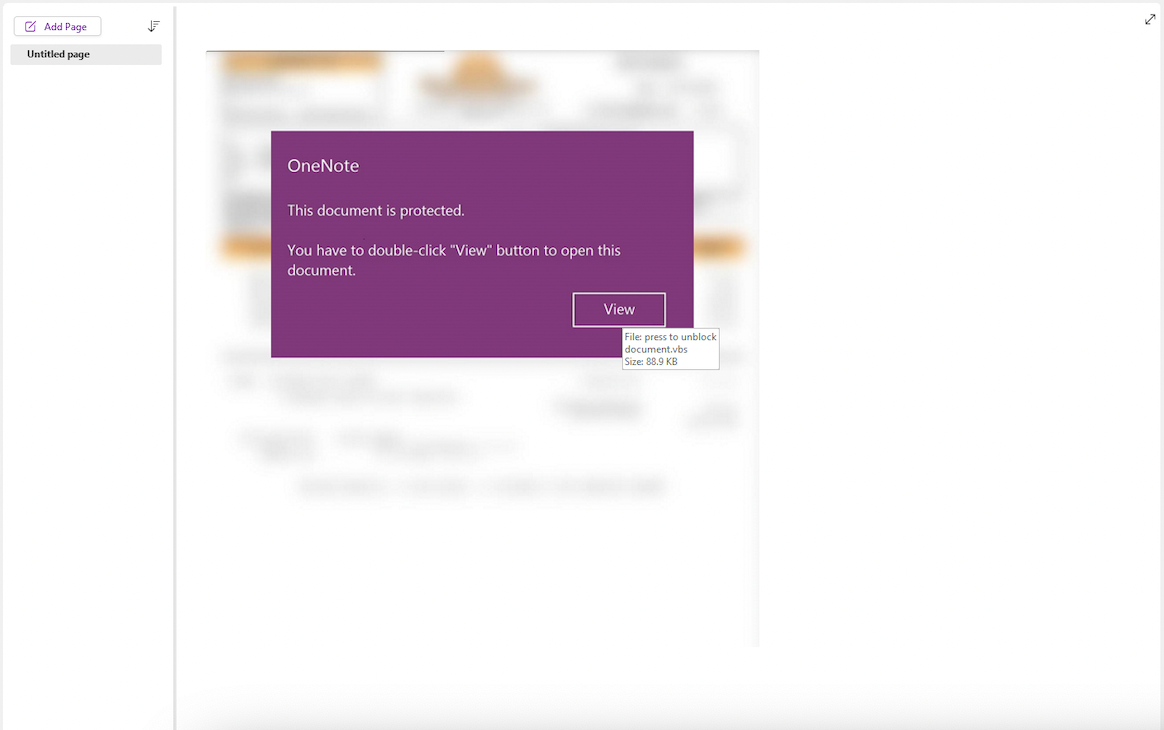

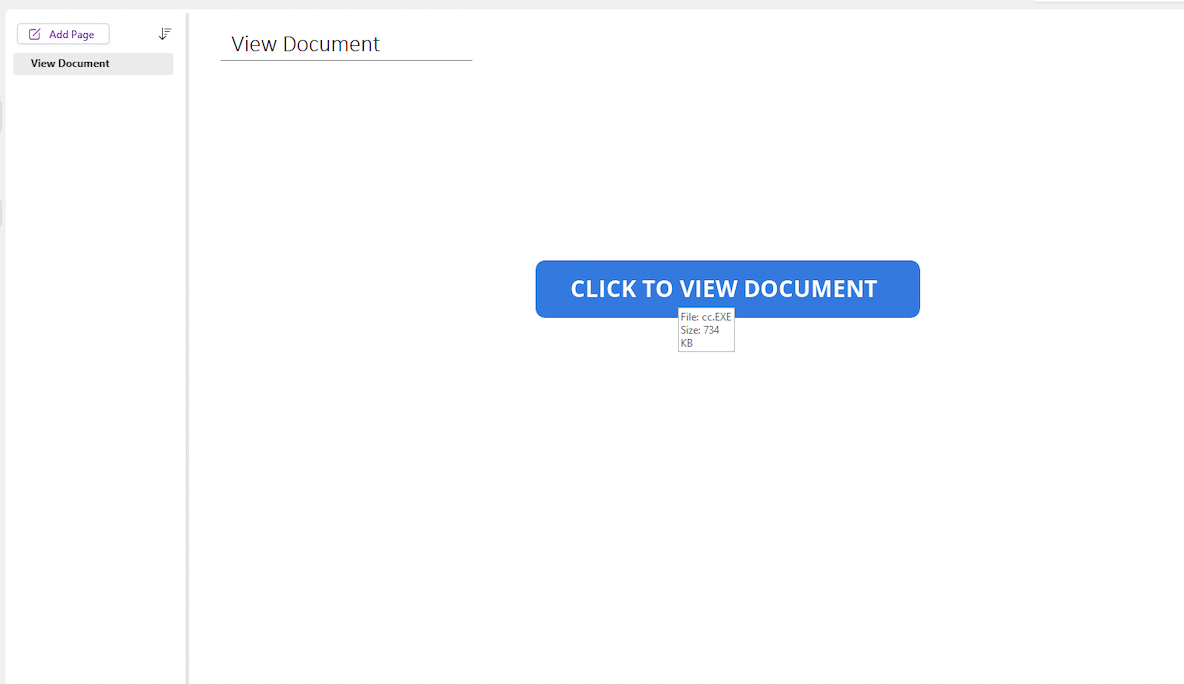

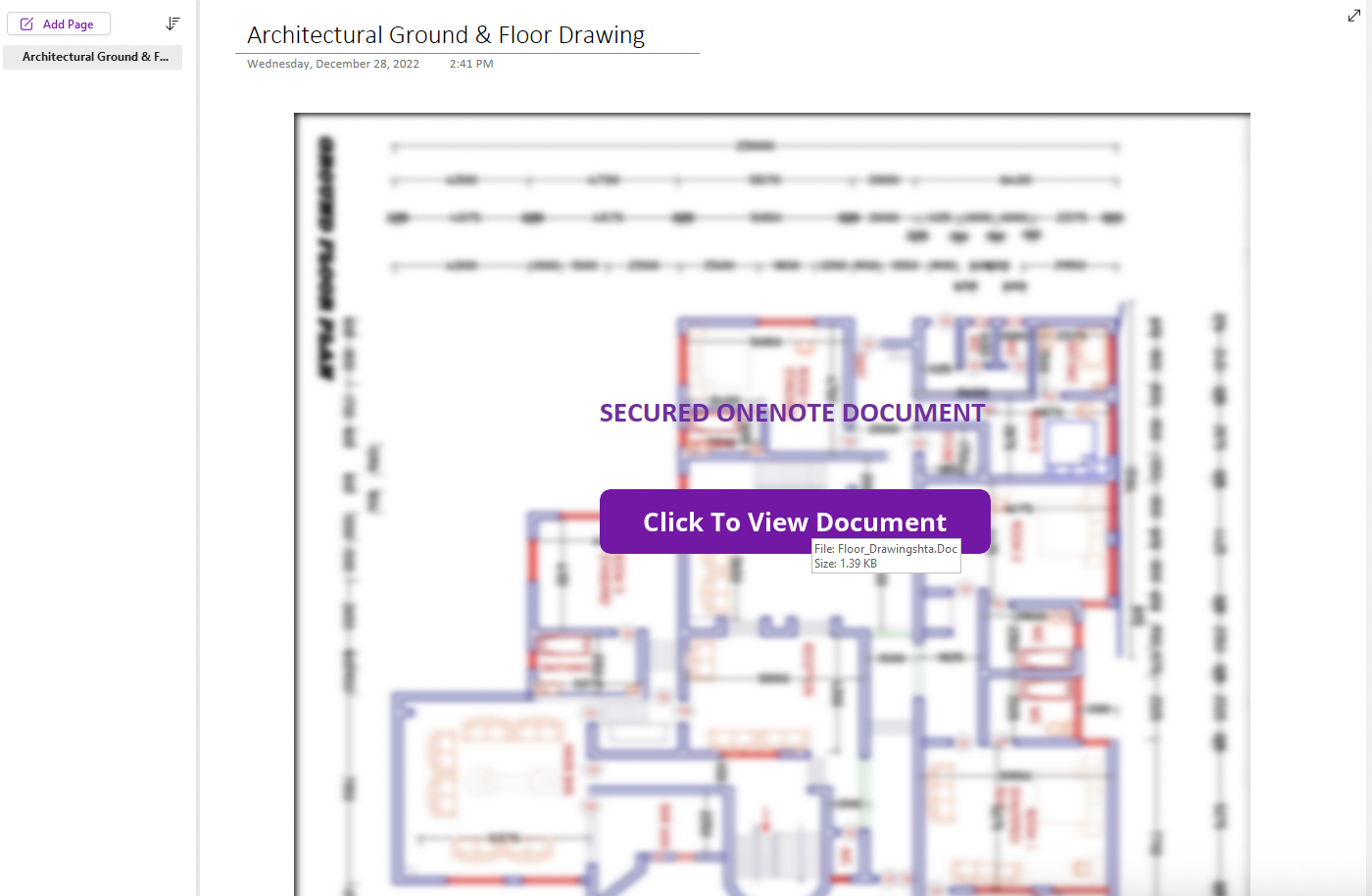

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show three different varieties of malicious OneNote samples with different types of embedded images and buttons. By hovering over the fake button, we can see the location and type of the payload planted in the OneNote file.

In Figure 1, the malicious OneNote sample asks the target to click on the view button to see the “protected” document. Upon doing so, a malicious VBScript file executes.

Similarly, Figures 2 and 3 show malicious OneNote documents with fake buttons that entice victims to execute an embedded EXE payload and an Office 97-2003 payload, respectively.

Methodology

As mentioned above, attackers mostly abuse OneNote files for malicious payload delivery. To do so, they tend to embed a few specific payload types such as the following:

- JavaScript

- VBScript

- PowerShell

- HTML application (HTA)

Despite the different file types, these payloads often show similar behaviors and aim to achieve the same malicious objectives. However, we won't delve into the entire attack and infection chain, as we have covered this in a previous article on malicious OneNote attachments.

The telltale sign of a malicious OneNote file is the presence of embedded objects. While benign OneNote files can also contain embedded objects, malicious OneNote files almost invariably include them.

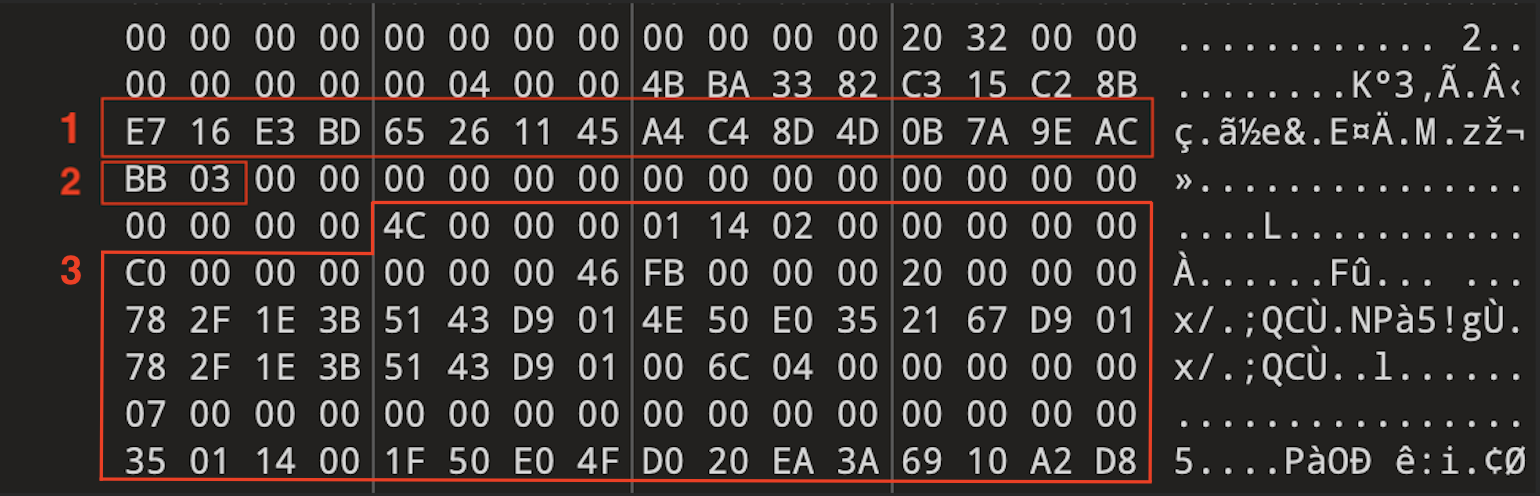

According to Microsoft, files embedded in OneNote start with a specific globally unique identifier (GUID) tag:

- {BDE316E7-2665-4511-A4C4-8D4D0B7A9EAC}

This GUID indicates the presence of a FileDataStoreObject object. The GUID is then followed by the size of the embedded file.

The actual embedded file follows 20 bytes after the aforementioned GUID tag and will be as long as the defined size. For example, in Figure 4 below:

- Box 1 represents the embedded object GUID tag

- Box 2 indicates the size of the embedded object

- Box 3 represents the actual embedded object

Payload Types and Average Size Distribution

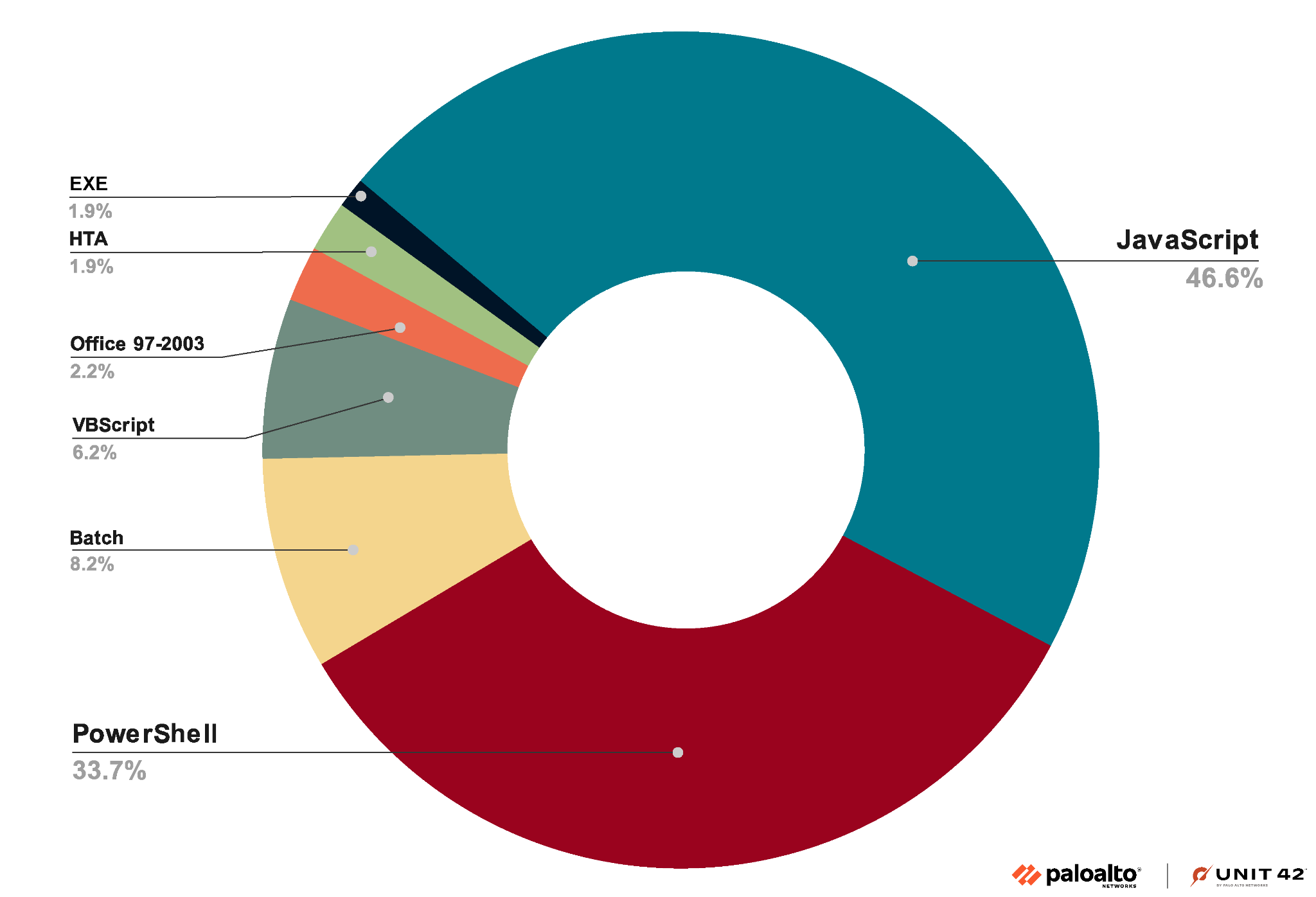

As illustrated in Figure 5, attackers predominantly use the following seven file types for their OneNote payloads:

- PowerShell

- VBScript

- Batch

- HTA

- Office 97-2003

- EXE

- JavaScript (this file type is the most commonly used)

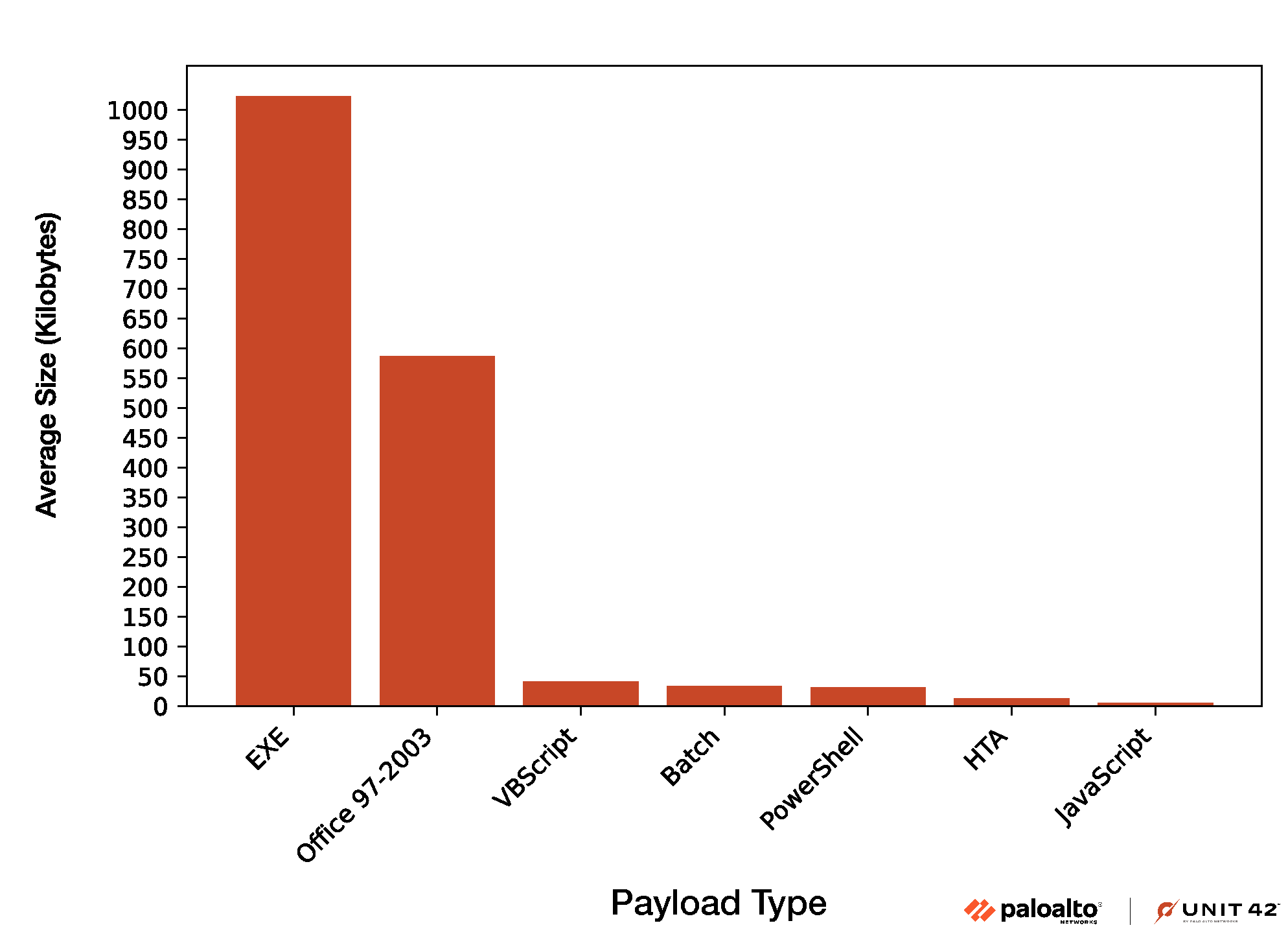

We also extracted and noted the size of each payload type, as shown in Figure 6.

While larger binary embedded payloads such as EXE and Office 97-2003 are more capable, attackers tend to use them less often (as shown in Figure 5) because they increase the overall size of the OneNote sample. Attackers tend to prefer a smaller overall file size, as smaller-sized malware is easier to include in common malware delivery mechanisms such as email attachments, thus raising less suspicion.

As illustrated in Figure 6 above, embedded malicious EXE and Office 97-2003 file payloads tend to be larger, and embedded malicious HTA and JavaScript files tend to be smaller.

Presence of Images in Malicious OneNote Samples

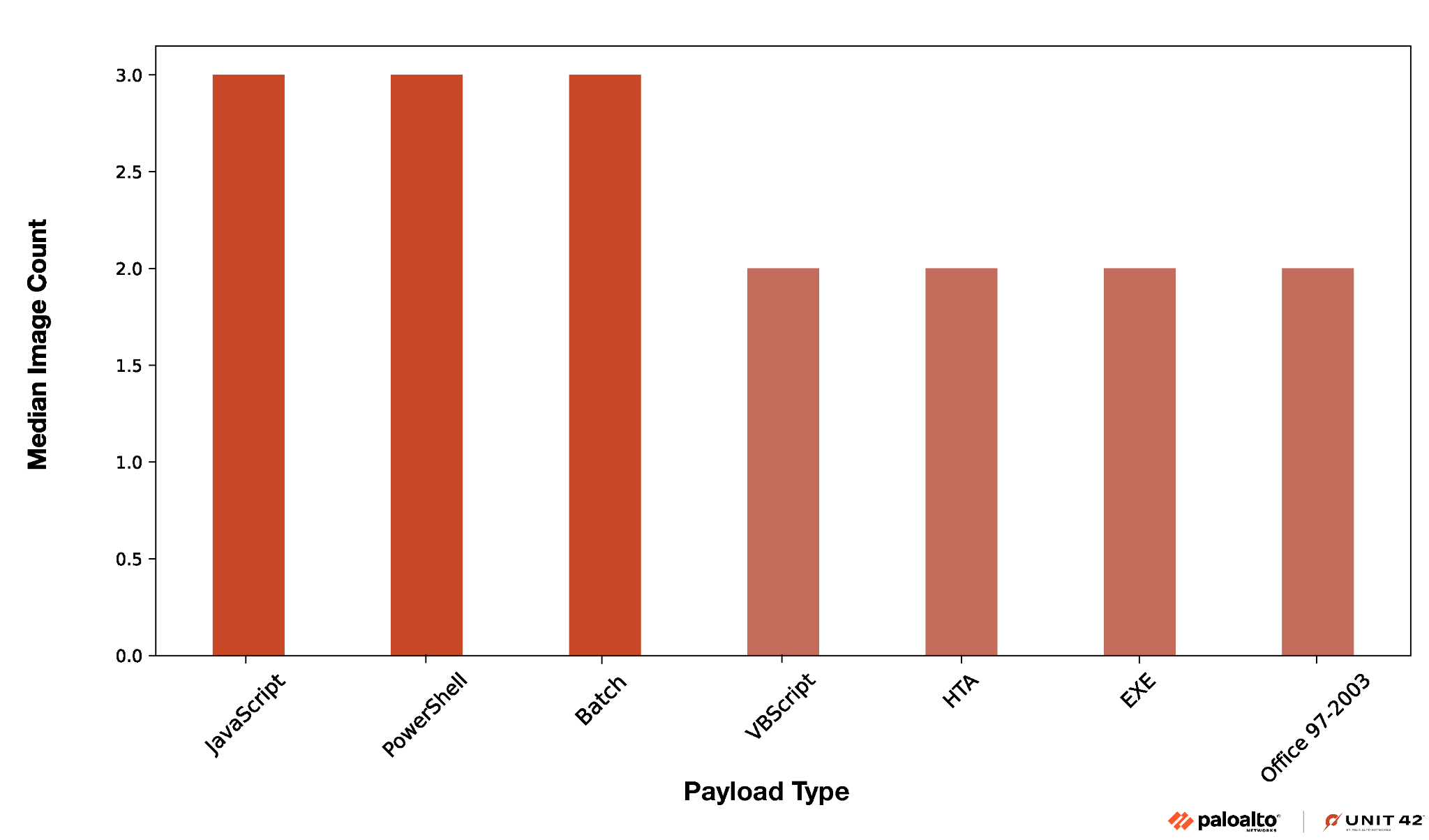

Attackers creating malicious OneNote lures use images that look like buttons to trick people into launching harmful payloads. We mapped out the number of images in each malicious OneNote sample with the payload type, and then calculated the median number of images.

In analyzing the 6,000 samples in our dataset, we found that all but three (99.9%) of the malicious OneNote samples contained at least one image. Since almost all of the samples contain at least one image, we can confirm our hypothesis that OneNote samples are primarily used as phishing vehicles.

Figure 7 shows that the median number of images per payload type is two. For instance, attackers could use both a fake button and an attention-grabbing image like a fake “secure” document banner to make their phishing campaign more believable (such as in Figure 3).

The chart above demonstrates that two to three images typically accompany payloads in malicious OneNote samples, some used to make the document more believable and some serving as fake buttons.

Analysis of an Embedded EXE Payload

While our previous research examined OneNote samples that carry the more common and popular payload types, such as PowerShell or HTA, EXE payloads have gotten less attention. In this section, we will analyze a OneNote sample with an embedded EXE payload.

The payload below is extracted from a OneNote sample with the following SHA256 hash:

- d48bcca19522af9e11d5ce8890fe0b8daa01f93c95e6a338528892e152a4f63c

The payload itself has the following SHA256 hash:

- 92d057720eab41e9c6bb684e834da632ff3d79b1d42e027e761d21967291ca50

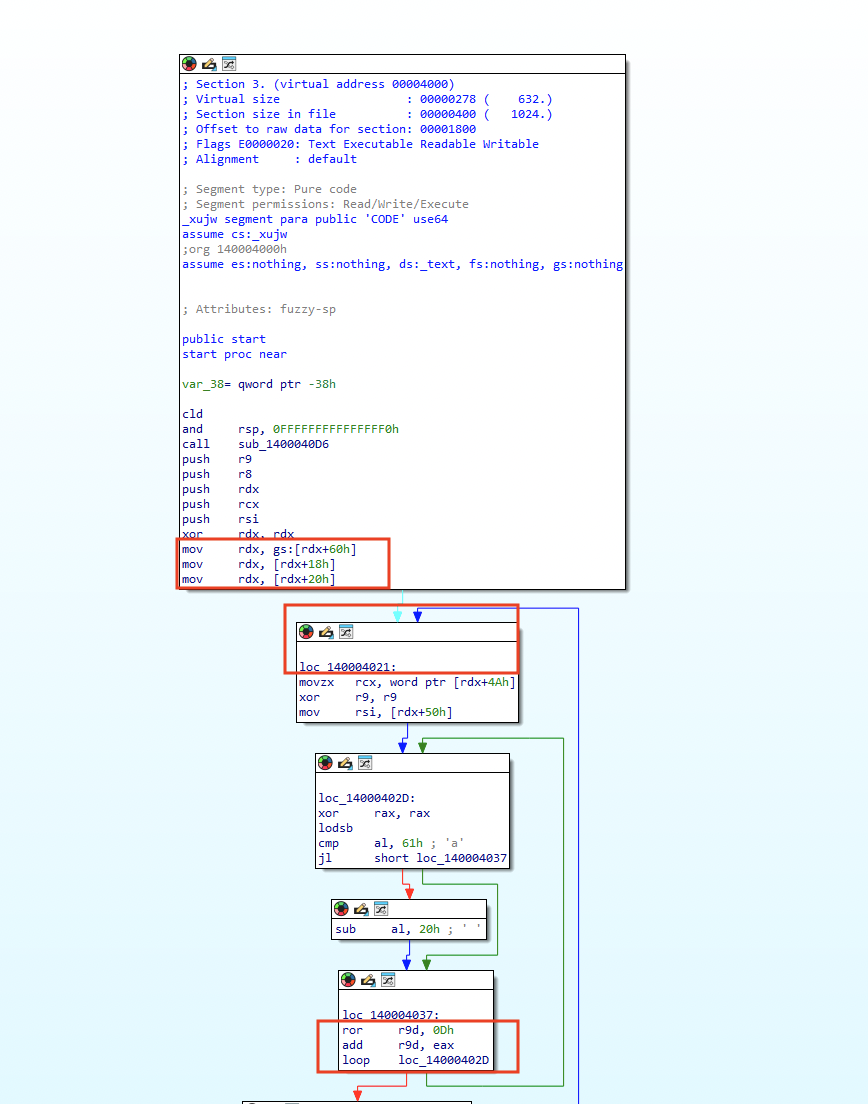

Figure 8 shows our analysis of the EXE payload in IDA Pro. We found a handful of code blocks, which often signal that we might be dealing with shellcode.

Our assumption was confirmed by the existence of GS:60, which points to the Process Environment Block (PEB) and the rotate right (ROR) instruction. This indicates that the malware is using dynamic address resolution for functions and hashing for function identification.

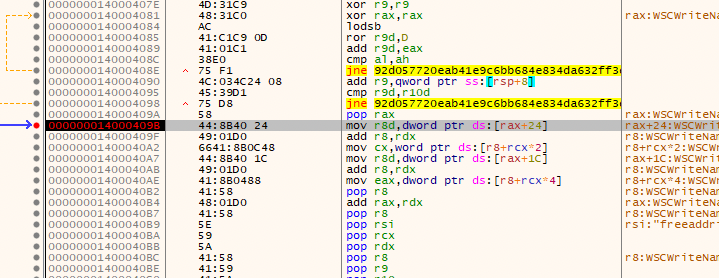

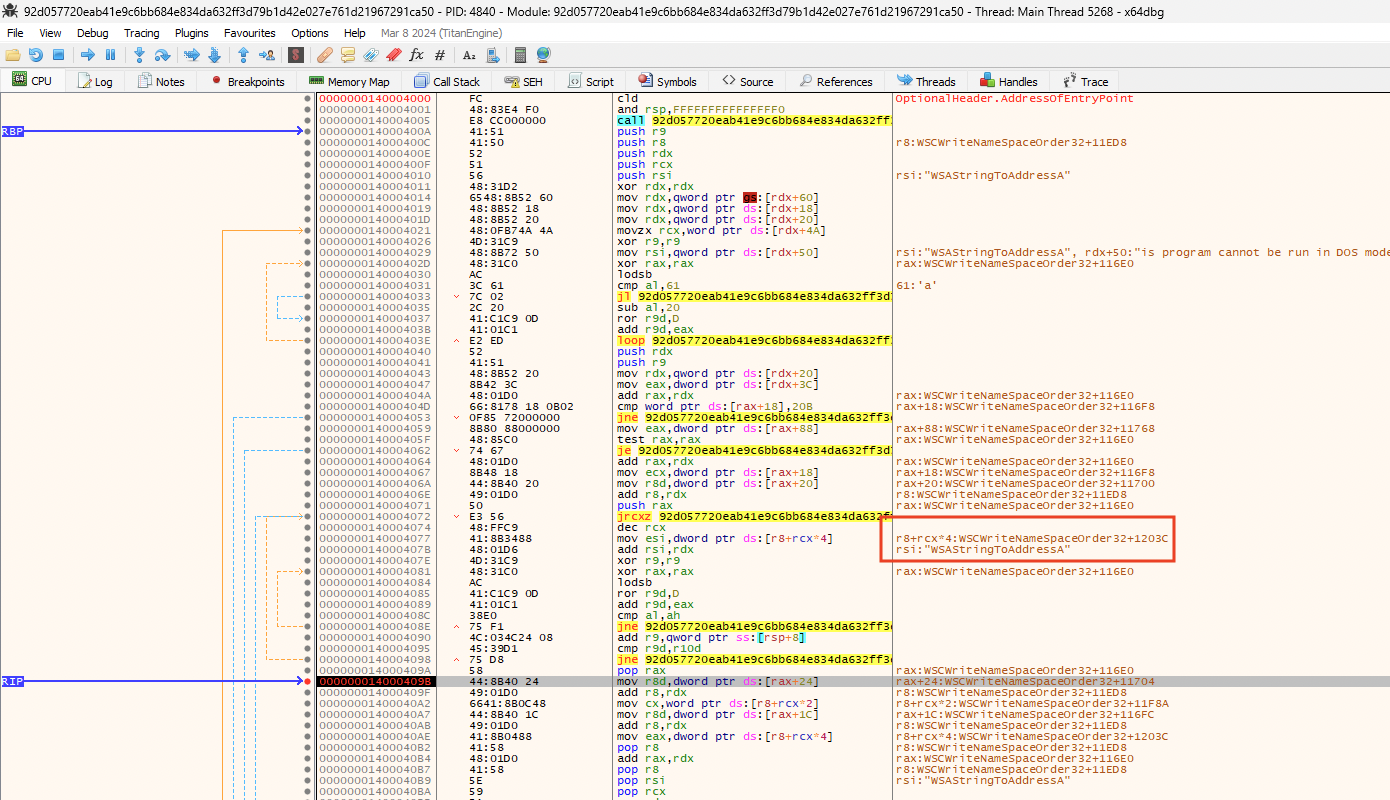

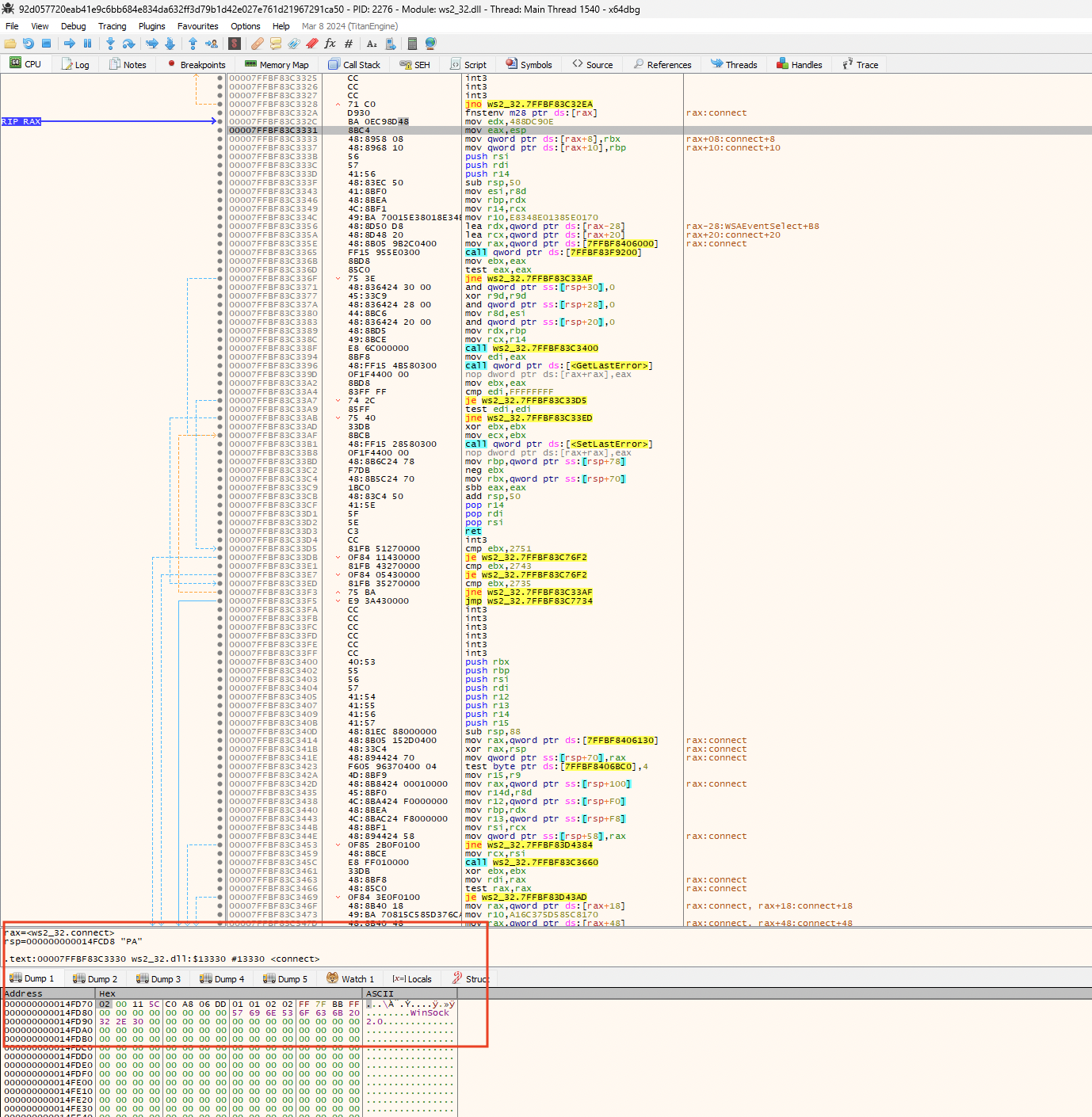

To get an understanding of the objective of the shellcode and identify the libraries it was dynamically loading, we opened it in the x64dbg debugger. We then put a breakpoint at the function that repeatedly calls the loc_140004021 function block in a loop, as shown in Figure 9.

The combination of the WSAStringToAddressA function (shown in Figure 10) and WSASocketW functions (shown in Figure 11) makes it clear that the shellcode is attempting to send or receive data by establishing a network socket.

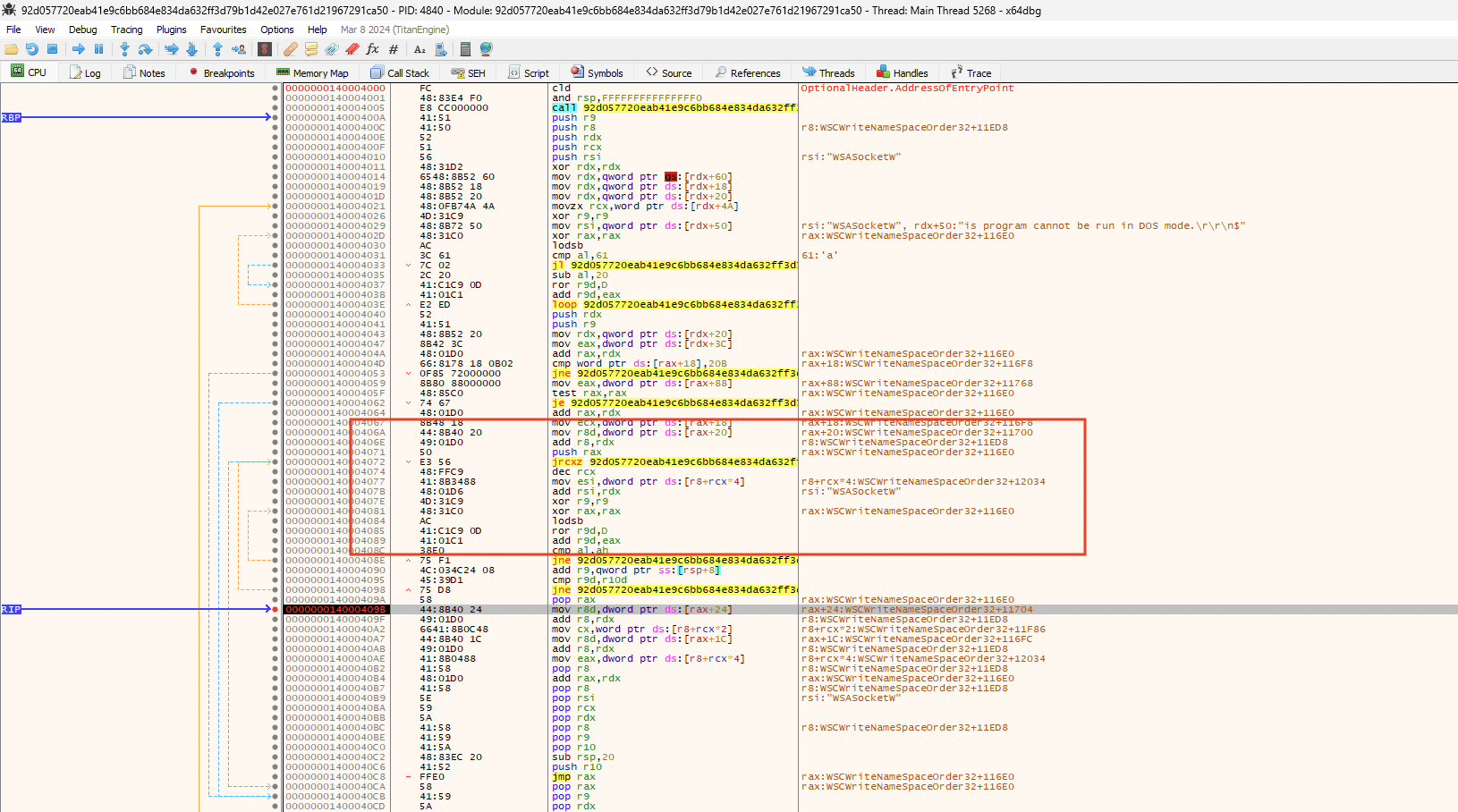

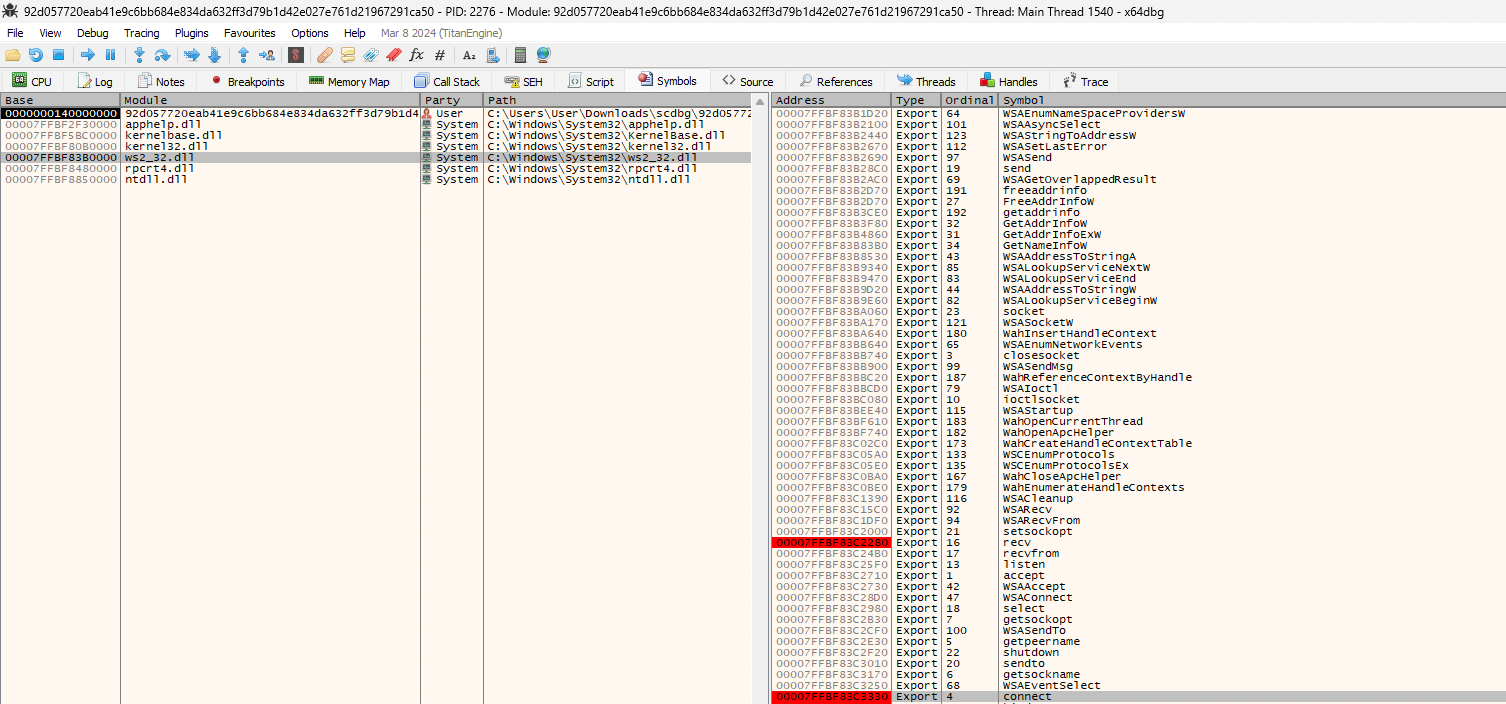

Since reverse TCP shells are the most common type of shellcode used for connecting back to the attacker's machine, we set up breakpoints in ws2_32.dll (shown in Figure 12) to determine whether the connect function is called. And if so, we could extract the arguments passed down to it. These arguments often have the IP address and port number to which the payload attempts to connect.

As expected, the shellcode stopped at the connect function call. Upon dumping the values of the RDX register, we were able to identify the contents of the sockaddr_in struct, as shown in Figure 13.

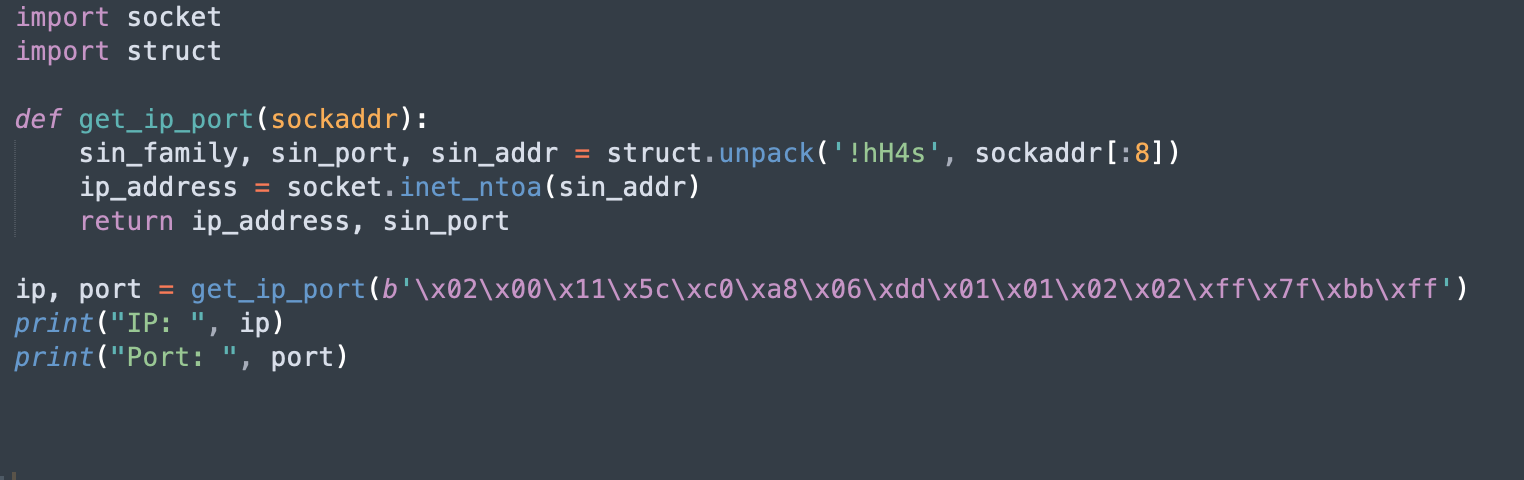

As shown in Figure 14, we then wrote a Python script to unpack the content of the sockaddr_in structure identified above.

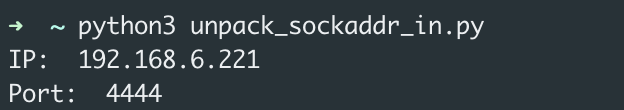

Executing the above Python script gave us the output shown in Figure 15, indicating the attacker is connecting to a local machine on port 4444, potentially to an attacker-controlled machine.

Conclusion

We conclude that OneNote as an attack vector is more versatile than we initially thought. It can carry executable payloads, in addition to script-based downloaders. Also, like many other file types, attackers can use it for lateral movement.

When embedding malicious payloads inside OneNote files, attackers mainly leverage JavaScript, PowerShell, Batch and VBScript. However, attackers occasionally use binary payloads such as executables or even Office 97-2003 files to achieve their objectives.

Organizations can consider blocking embedded payloads with dangerous extensions within OneNote files to protect their users against such attacks. More broadly, we recommend people limit their exposure by checking the embedded payload filenames and extensions in OneNote files by hovering over any buttons or images before clicking them.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed above through the following products:

Indicators of Compromise

The following are links to our Github repository containing file hashes for the OneNote files and payloads discovered during our research for this article.

Additional Resources

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

from Unit 42 https://ift.tt/T1vNhFR

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment