Executive Summary

We investigated 19 new top-level domains (TLDs) released in the past year, which revealed large-scale phishing campaigns, distribution of potentially unwanted programs, torrenting websites, and even pranking and meme campaigns.

We saw correlation between the new TLDs' general availability dates and their popularity, showing that different groups follow the launch of new TLDs and their lifecycle. They do so to initiate domain registration and usage, including for abuse.

There are currently over 1,000 generic top-level domains (TLDs) according to the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) root database, and more new TLDs are being added every year. As new TLDs emerge, the potential for malicious activity such as domain squatting and phishing increases tremendously. This is especially problematic when these TLDs resemble the extensions of popular file extensions such as .zip, and distinctive service identifiers such as .bot.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed in this article through our Network Security solutions, such as Advanced DNS Security and Advanced URL Filtering subscription services.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Malicious Domains, Newly Registered Domain |

New TLDs

The IANA root database currently lists over 1,000 generic top-level domains (TLDs), with new additions continually being made each year. New TLDs under the Generic TLD (gTLD) category are added for myriad reasons including promoting new markets, allowing brands to diversify their web presence, and increasing consumer and business choices.

In the past year and a half, 19 new TLDs have been announced. As more new TLDs are released, companies and other entities may have a hard time keeping up and defensively registering their names on all of them. This presents a possibility for attackers to exploit these TLDs, especially those that resemble file extensions, repurposing them for malicious activities.

TLD Rollout Phases

To understand the potential negative effects of these new TLDs and domain registrations, we first need to understand how new TLDs are rolled out.

All domains under a TLD are tracked in an authoritative database called a registry. A registry operator is the organization that maintains this authoritative database of all domain names for a particular TLD.

After new TLDs are delegated and approved for future release, the registry operator associated with the new TLD takes responsibility for the different launch and registration phases. A typical set of launch phases will include the following:

Note that while these phases are typically associated with generic TLDs, only the sunrise period and general availability are mandatory.

Sunrise Period

This is a mandatory phase for all registries. In this phase, registrations are open only to holders of a validated trademark record in the Trademark Clearinghouse (TMCH). This is an effort to help entities secure domain names under new TLDs that fall under their trademark to protect them from cybersquatting and domain squatting attacks according to ICANN Wiki. If more than one entity proves claims to a certain domain, an auction is conducted.

There are two types of sunrise periods:

- End date sunrise (minimum 60-day length)

- The less common Start date sunrise (30-day notice before the start of sunrise period and 30-day minimum length)

Landrush

The landrush phase allows registry operators to make registrations open to the public for specific, premium domain names at a higher cost than their price during general availability. Multiple parties applying for the same domain may lead to an auction.

Early Access Period/Program

Certain TLDs also have an early access period that lasts about a week. Some registry operators may not differentiate between the landrush and early access periods (EAP), and others may offer EAP-like pricing during the first week of general availability.

During the EAP, registrants have the opportunity to register a domain name at a premium price before the TLD's official launch during the general availability period on a first-come, first-served basis. The registry operator may set a premium price that is determined based on the number of days starting from the beginning of this period. The first day of early access has the highest registration price and the last day has the lowest, but both are still higher than the general availability period price.

General Availability

Finally, the TLD is officially launched and moves to a general availability phase where domains under this TLD are available to the public for registration. As mentioned before, some registry operators may offer EAP-like pricing during the first weeks of general availability where domains can be registered for a premium price that slowly drops throughout this period. Typically, a trademark claims phase is in effect in the first 90 days of the general availability period where trademark holders could be alerted when someone registers a domain name matching their trademark.

Data Sources

We track the release of new TLDs through the official ICANN website, which reports the sunrise dates for all generic TLDs.

In particular, we are focusing on 19 TLDs that have been released or are in the process of reaching general availability:

- .bot

- .box

- .case

- .channel

- .dad

- .esq

- .foo

- .ing

- .lifestyle

- .living

- .meme

- .mov

- .music

- .nexus

- .phd

- .prof

- .vana

- .watches

- .zip

In April 2024, we gathered data about domains under these TLDs from a variety of sources: passive DNS, zone file data published by registry operators, historical newly registered domains (NRDs) and historical domain squatting detections in these TLDs. Finally, we augment this list by taking the top 1 million most popular domains on the internet using the Tranco list—a research-oriented top site ranking. We replace their TLD with each of the 19 new TLDs in an effort to cover all potential cases of abuse of the most popular domain names.

Traffic Toward Domains in These New TLDs

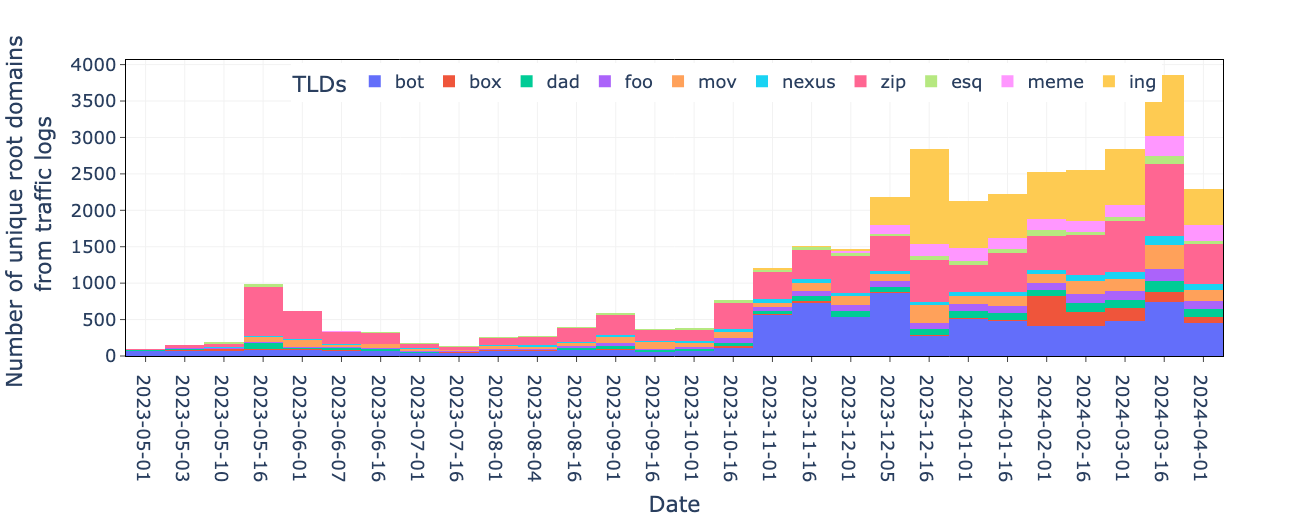

From our customer data logs, Table 1 shows the most-popular new TLDs with the number of unique registered (root) domains.

| TLD | Number of Registered Domains |

| .zip | 5,470 |

| .ing | 5,071 |

| .bot | 4,179 |

| .mov | 1,279 |

| .meme | 1,175 |

Table 1. Most popular TLDs from our customer data logs.

We sampled our traffic logs two times a month and added some important dates from the TLD launch schedule as displayed below in Figure 1. This data indicates that the rise in popularity of the top 10 TLDs correlates with the date that a TLD enters the general availability phase.

The .zip TLD entered general availability on May 10, 2023. From the data on May 16, 2023, we see the first spike in the popularity of the .zip domains.

The .ing TLD entered general availability on Dec. 5, 2023. On that same day we saw a large spike in traffic toward .ing domains that has continued since then.

Similarly, Amazon initially allowed registration of .bot domains to customers exclusively for bot-related services. After the .bot TLD entered general availability on Oct. 30, 2023, our data reveals notable increases in .bot domain registrations starting on Nov. 1.

The evident correlation between these new TLDs' availability and the number of domain registrations indicates that various groups or individuals closely follow the launch of new TLDs to register new domains. These groups could include adversaries that plan to abuse domains belonging to these newly available TLDs. Therefore, tracking and conducting security checks for domains under emerging TLDs is crucial.

Introducing Our Graph-Based Detection System

Our graph-based detection system is enabled by a powerful internal graph database that ingests comprehensive cybersecurity data from various data sources including the following:

- Passive DNS data

- WHOIS

- Third-party threat intelligence sources

- Static and dynamic analysis of malware samples

- Active web crawl data

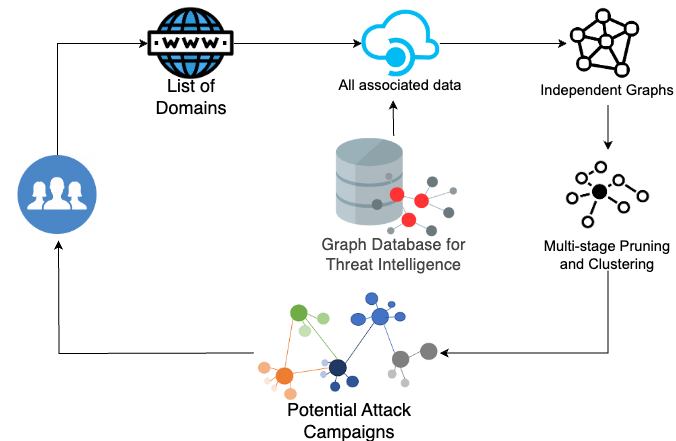

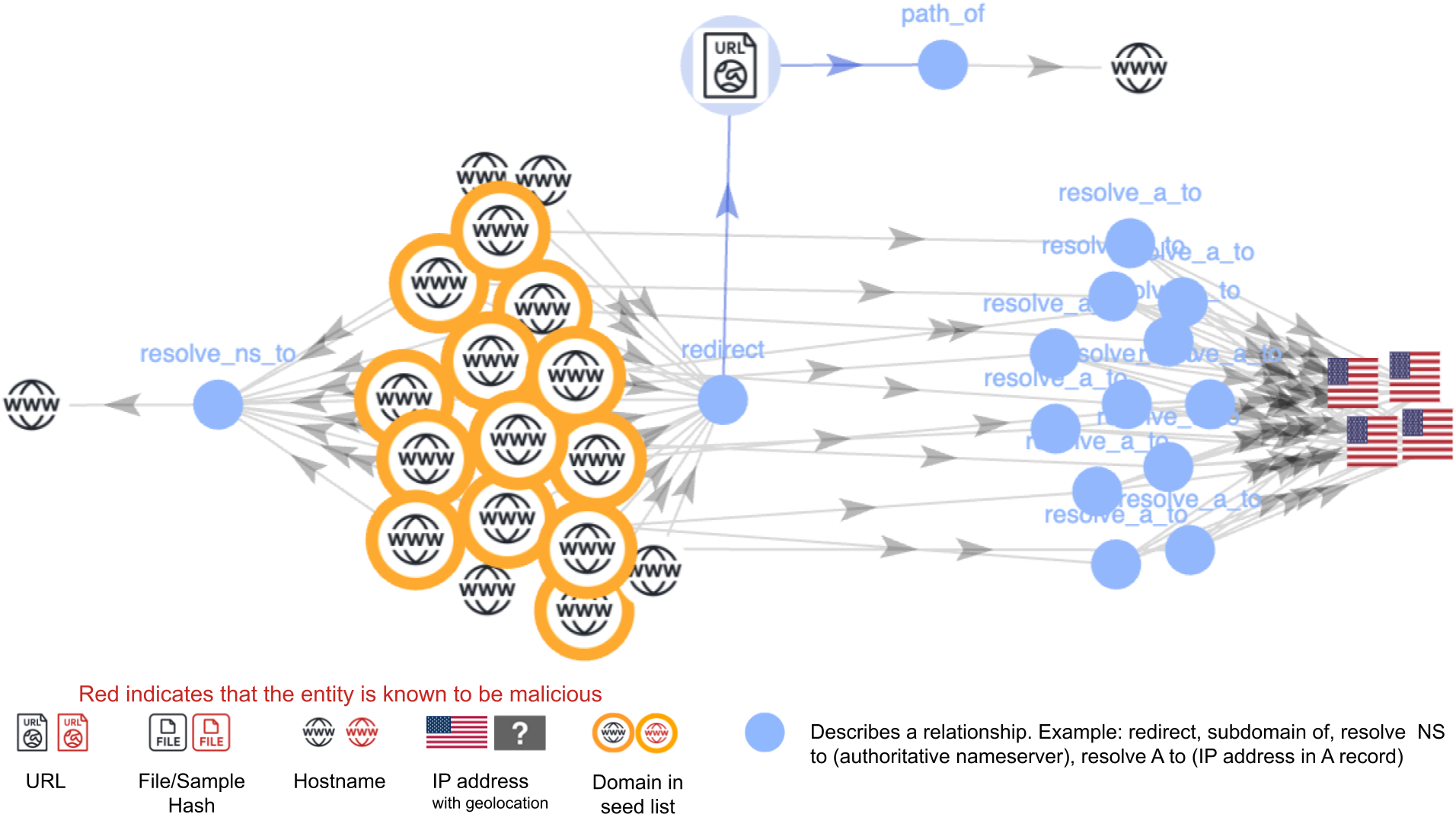

Leveraging these data sources, we developed a graph-based automated detection system depicted in Figure 2. Starting with a seed list of domains, the system extracts all related data, including associated URLs, IPs and malware samples.

The system generates an independent graph visualization for each seed domain that depicts the relevant relationships with these other associated entities. In this case, the seed list was a list of all domains under these 19 TLDs that we obtained by analyzing information from our previously mentioned data sources.

After constructing the graph relations, we conduct a multi-stage pruning and graph clustering process. In this process, our system’s pruning algorithm significantly reduces noise and redundancies, only retaining the salient graph paths.

For instance, if a domain uses a globally popular nameserver, then hundreds or thousands of other domains will also use the same nameserver. This results in extra noise added to the graph due to that nameserver node. To address this problem, we prune all paths that are connected to a list of known, benign and popular nodes.

Next, we put these pruned graphs through a clustering process that hunts for commonalities. Our system can cluster domain graphs together based on specific features such as the following:

- Related IP addresses

- Authoritative name servers

- Their WHOIS information

- Domain name lexical patterns

- Traffic and redirection patterns

- TLS certificate information

- Shared or common web infrastructure and content

This process helps us correlate campaigns that share the following traits:

- The same infrastructure

- The same traffic distribution systems

- Downloading and disseminating the same malware samples

- Abusing a common set of intermediary services to broaden their attacks

Results: Case Studies

In this section, we present select network abuse campaigns captured by our graph-based detection system. The results include the following:

- Large-scale phishing attacks

- Distribution of potentially unwanted programs

- Torrenting websites

- Pranking or meme campaigns

Redirection Campaign

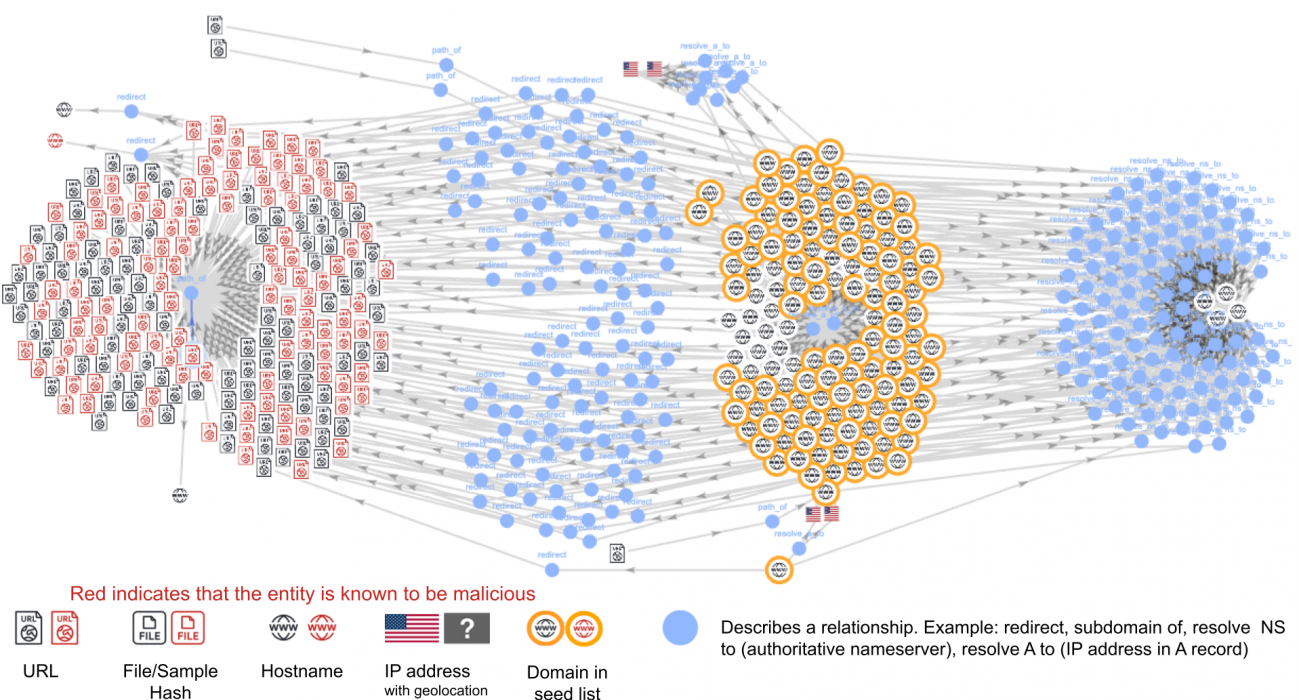

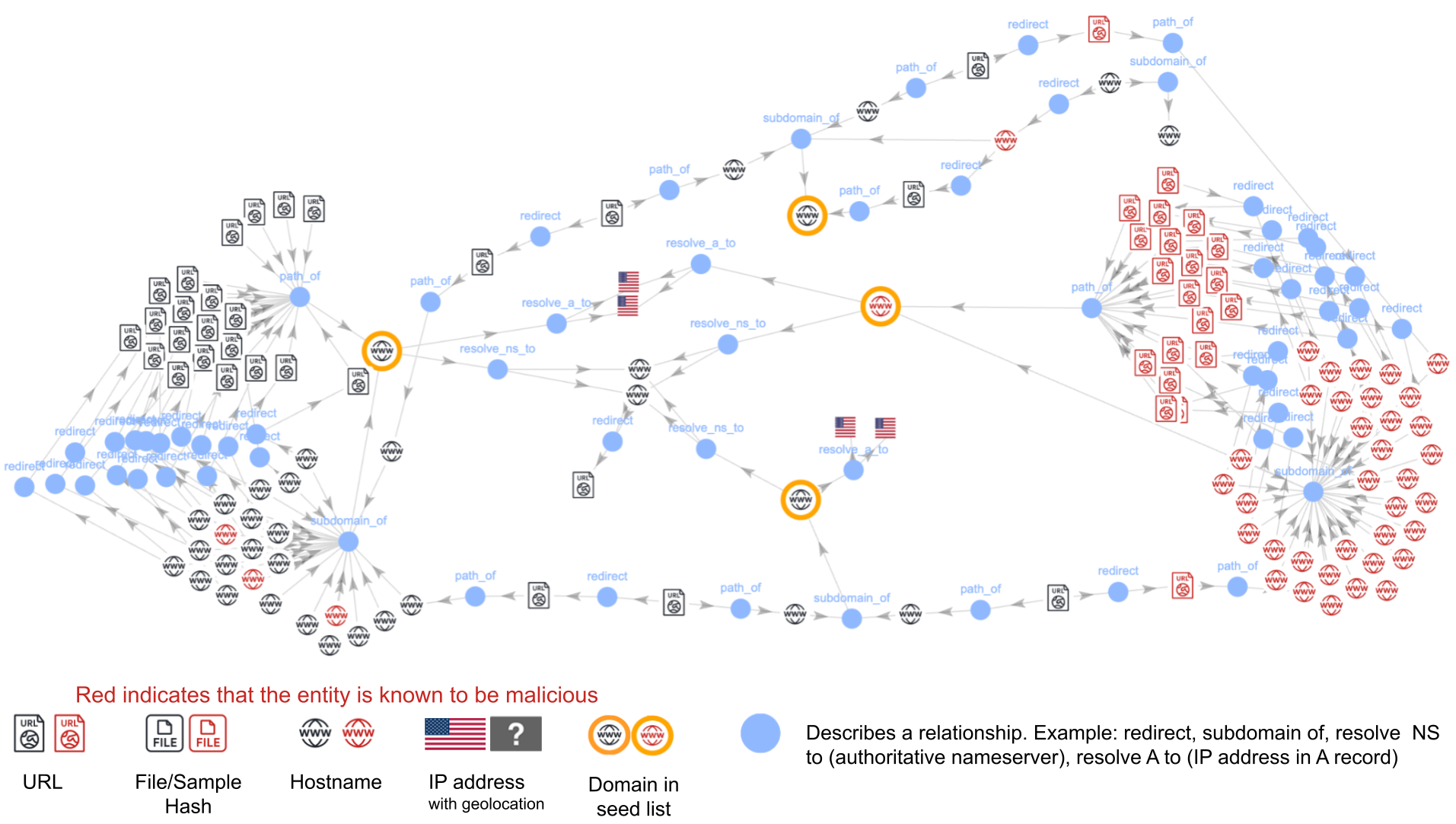

Bad actors can leverage trending TLDs and domain names to propagate phishing and redirection attacks. In one such case study, we found that 112 domains belonging to these new TLDs form a tightly related cluster that can be associated with a phishing campaign.

Below, Figure 3 shows the clustered graph for this campaign. The nodes near the middle highlighted in yellow are domains under the newly released TLDs. The red nodes are known malicious indicators that our detectors have already blocked for other suspicious activity or content.

Each blue node represents a relationship between two entities, such as URLs, hostnames, IP addresses and files. Figure 3 reflects four distinct types of relationships in the graph:

- NS records for the domain

- A records for the domain

- Redirect to a URL

- URLs sharing a “path of” relationship with their root domain

At the time of our data collection, all 112 domains redirected to different URL paths under the choto[.]xyz domain.

Although active as recently as April 2024, by May 2024, this traffic coordination domain choto[.]xyz was inactive and returned an NXDOMAIN DNS error. Checking our archived scans and web archive data, we find that these paths had redirected users to a gambling website.

We found these 112 domains subsequently redirected to URL paths under choto[.]click/vx/<string> that redirected to gambling websites. Figure 4 shows an example of one of the gambling pages.

All 112 domains share the same four nameservers that are denoted by the nodes on the far right in Figure 3. These nameservers are hosted on the same set of IP addresses, indicating a shared infrastructure.

All 112 domains were also registered with the same registrar, with most registered from June-November 2023. We are the first to detect and block over 78% of these 112 domains according to data from open threat intelligence platforms.

Data from this campaign indicates the group behind it has expanded beyond leveraging newly released TLDs. Our analysis also reveals targeted keywords surrounding recent events. For example, we found at least four new domains relating to the 2024 Summer Olympics are connected to this same campaign.

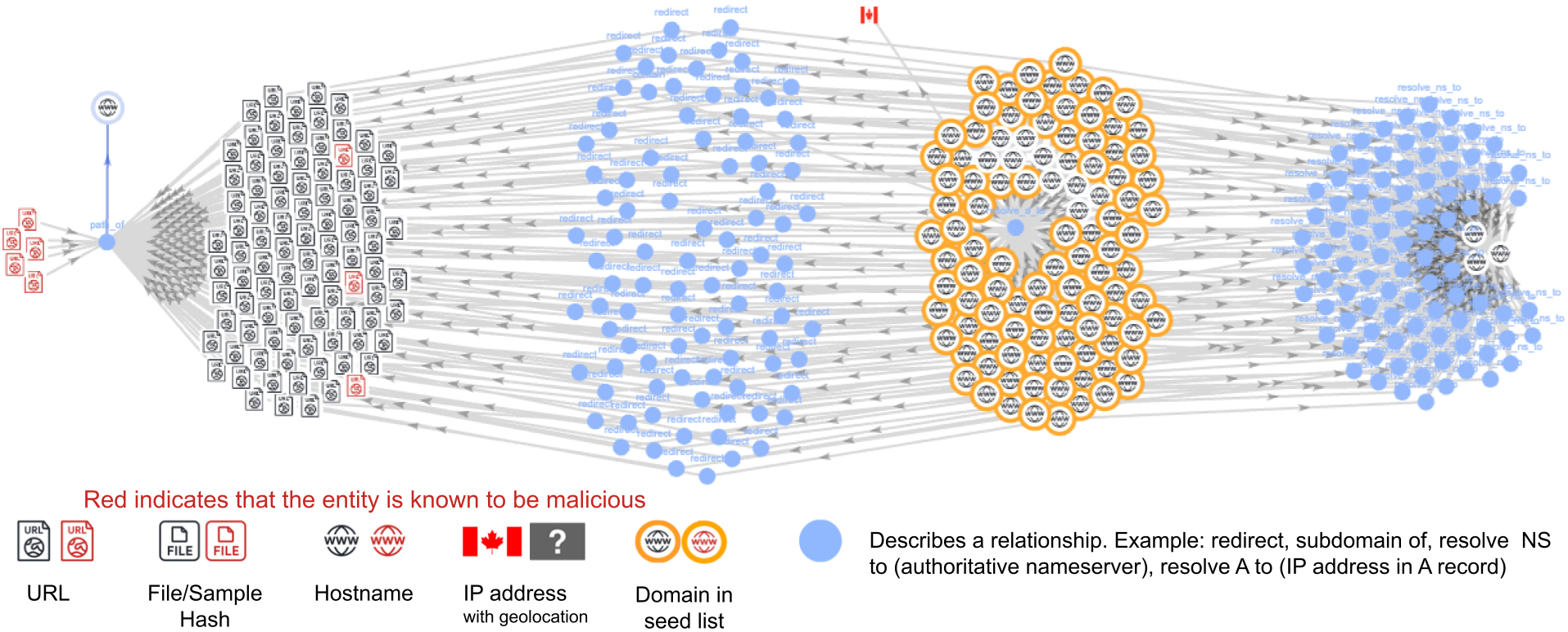

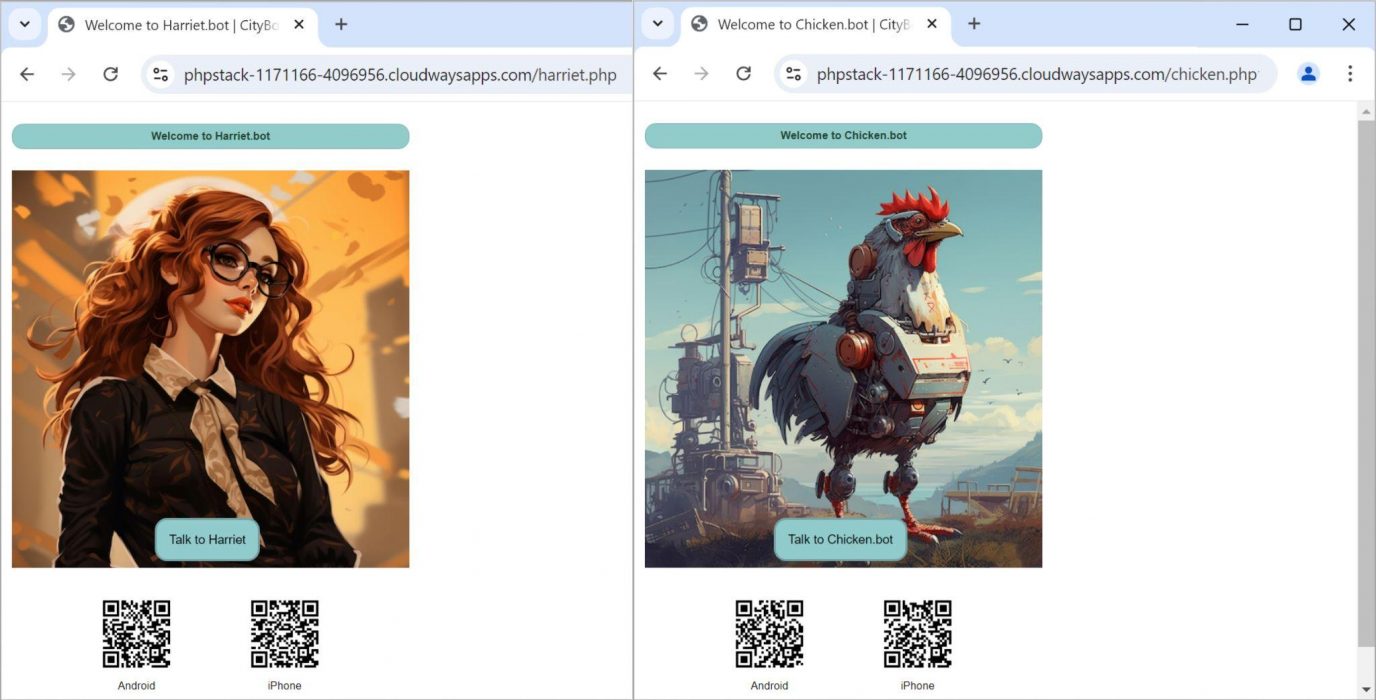

Chat Bot Service Campaign

Another cluster involved luring victims into scanning a QR code that redirects them to begin texting over SMS. The SMS session can potentially expose the victim to scams, spam, data harvesting campaigns and exposure of personal information.

Shown in Figure 5, this campaign contains 92 different domains belonging to the .bot TLD. The domains in this cluster have distinct naming patterns. They are either:

- A person’s first name (such as Akira, Emilia, Mei, Percy or Valentina)

- The name of a city (such as Amsterdam, Leipzig or Toronto)

- Random German words (such as Fluege, Kleinanzeigen, Termin or Welt)

- Random English words (such as Broadband, Chicken or LastMinute)

All of these .bot domains redirected victims to a URL under a different domain ending with the same root name string suffixed by .php.

For example, the domain harriet[.]bot redirected to the URL at phpstack-1171166-4096956.cloudwaysapps[.]com/harriet.php

Figure 6 illustrates how the picture/avatar displayed and the QR code changes in relation to the domain name queried.

Similar to the previous campaign, all 92 domains share three nameservers hosted on the same IP address. All 92 domains were registered with the same registrar. Notably, all 92 domains were all registered within a two-week period between Nov. 11, 2023, and Dec. 3, 2023, all within five weeks of the

.botdomain entering general availability.

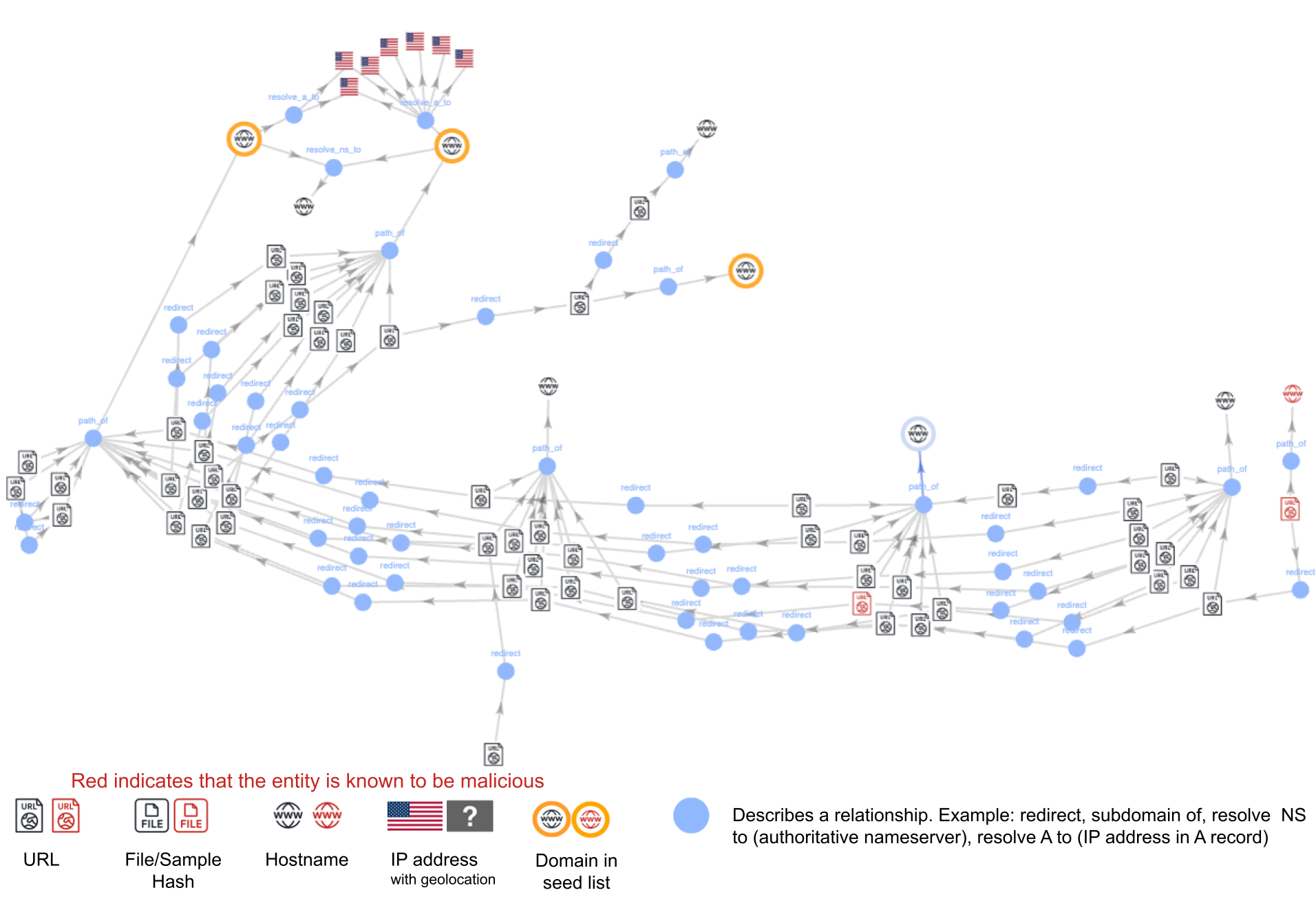

Torrenting Unblockit Cluster

Investigating homogeneous clusters, we found a campaign distributing pirating and torrenting links that contain four domains using the same root name with four different TLDs:

- .esq

- .zip

- .ing

- .foo.

URLs under these domains all have similar paths as well.

Our graph-based analysis reveals that the infrastructure of these torrenting services keeps evolving as its domains are blocked by security vendors. Figure 7 indicates URL paths that redirect users to the same path under a different TLD, possibly as a mirroring phenomenon.

Following this pattern, we found websites with the root name unblockit under different TLDs. We found 11 additional domains that all redirected to the same unblockit torrenting webpage.

Similar to the above cluster, we found another campaign that uses the root name worldfree4u with different TLDs, which is a torrent and piracy distribution website. Figure 8 shows that we observed the same domain name under five different TLDs:

- .foo

- .meme

- .mov

- .zip

- .dad

Figure 8 reflects a serial chain of redirections of URLs from one domain under one TLD to another.

Examining Previously Reported Malicious TLDs and Domains

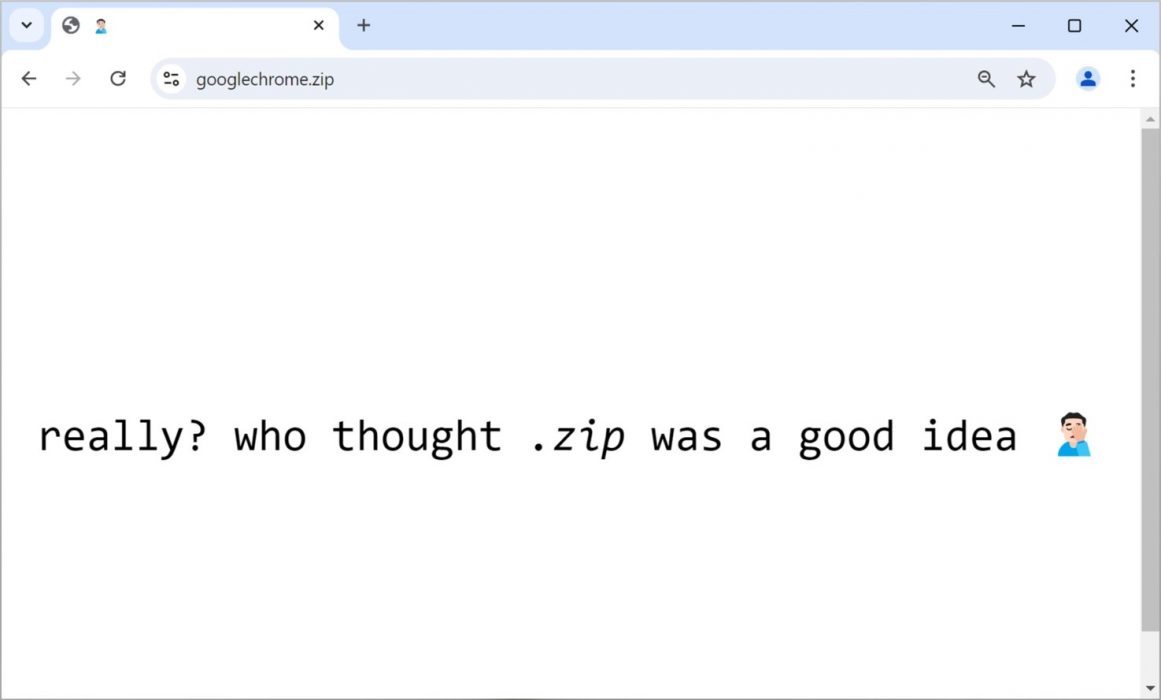

Of all the newly released TLDs, .zip and .mov are two TLDs that are among the 10 most popular that also resemble popular file extensions. When Google released these two TLDs for general availability in May 2023, many sources commented on the dangers of these TLDs and how attackers were already leveraging them to perpetuate phishing attacks. Consequently, many of these domains were blocked by security vendors, and new domains under these TLDs began to be scrutinized more carefully.

Malware, Critiques and Pranks

We analyzed previously reported malicious .zip domains and found they have either become NXDOMAINs, parked pages or result in network traffic errors. Some of these previously malicious domains redirect to pages critiquing the TLD, like latestupdate[.]zip and googlechrome[.]zip. Figure 9 illustrates an example of the critique sites.

Websites from domains using the .zip TLD can automatically offer ZIP archives for download. These ZIP archives can contain anything, depending on who established the web server.

Some domains previously reported as malicious now contain prank content. For instance, assignment[.]zip downloads a ZIP archive that contains a picture of a leek and one music track (mp3 file), while photos[.]zip simply contains the text: “haha you got phished!”

At least two servers using .zip TLD domains previously reported as malicious currently distribute content flagged as malware. The first is eicar-test-file[.]zip that appears to send a randomly named ZIP archive containing an EICAR test file.

The second is bomb[.]zip, a site that critiques ICANN's decision to approve the .zip TLD. It states "We heard you like zip bombs!" and sends a zip bomb.

From our studies, we see that many .zip and .mov domains are being used for pranks and memes such as rickrolling.

Leveraging TLDs That Look Like File Extensions for Trolling

We also observe that domains, specifically ones that appear to be file extensions, are increasingly used for trolling online. Specifically for rickrolling, we observed 13 domains in this cluster under the TLDs .zip and .mov redirected users to a bit[.]ly link that led to a YouTube music video of a 1987 song titled “Never Gonna Give You Up” by musician Rick Astley.

These 13 domains resemble file names such as attachedpdf[.]zip and testvideo[.]mov. All of them point to the same set of nameservers denoted by the node on the left in Figure 10. They also have the same four IP addresses in their A record, indicated on the right in Figure 10.

Conclusion

We investigated domains registered under 19 newly released TLDs from the past year. To sustainably track the evolution of these domains over time, we introduced our graph-based investigation pipeline that can help identify coordinated attack and misuse campaigns.

This article presented detailed case studies on a variety of cyberthreats to show how domains registered on these newly released TLDs have been used for redirection, chatbot campaigns and torrent distribution. As new TLDs emerge, the potential for malicious activity such as domain squatting and phishing increases. This investigation reveals the importance of monitoring domains registered under new TLDs to discover and track new trends and attack campaigns.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers receive protections against malicious indicators (domain, IP address) mentioned in this article via Advanced DNS Security and Advanced URL Filtering subscription services.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

The following are domains and URL paths related to this article.

- akira[.]bot

- amsterdam[.]bot

- attachedpdf[.]zip

- broadband[.]bot

- chicken[.]bot

- choto[.]click

- choto[.]click/vx/

- choto[.]xyz

- crowdstrike-hotfix[.]zip

- crowdstrikefix[.]zip

- emilia[.]bot

- fluege[.]bot

- harriet[.]bot

- kleinanzeigen[.]bot

- lastminute[.]bot

- leipzig[.]bot

- mei[.]bot

- percy[.]bot

- phpstack-1171166-4096956.cloudwaysapps[.]com/chicken.php

- phpstack-1171166-4096956.cloudwaysapps[.]com/harriet.php

- termin[.]bot

- testvideo[.]mov

- toronto[.]bot

- unblockit[.]black

- unblockit[.]esq

- unblockit[.]foo

- unblockit[.]ing

- unblockit[.]zip

- valentina[.]bot

- welt[.]bot

- worldfree4u[.]dad

- worldfree4u[.]foo

- worldfree4u[.]meme

- worldfree4u[.]mov

- worldfree4u[.]pm

- worldfree4u[.]zip

- assignment[.]zip

- photos[.]zip

- bomb[.]zip

- eicar-test-file[.]zip

from Unit 42 https://ift.tt/LdeIgn4

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment